Throughout the Upper Amazon, a shaman’s power — the power both to heal and to harm — is conceptualized as a slimy or sticky substance, sometimes corrosive, which is kept in the shaman’s chest. Mestizo shamans call this substance simply la flema, phlegm, or llausa, the ordinary Quechua term for phlegm, or yachay, the Quechua word for ritual knowledge. It is in this phlegm that the shaman, whether healer or sorcerer, stores the magic darts that are used for both attack and defense; in the phlegm of the sorcerer are also toads, scorpions, snakes, insects, monkey teeth, razor blades — the biting, the stinging, and the venomous.

|

What is striking about this is that shamanic power is a physical object inside the body, capable of storage, projection, and transmission. The virtually universal method of inflicting magical harm in the Upper Amazon is to project this substance into the body of the victim — either the substance itself or the pathogenic projectiles the shaman keeps embedded within it. And the virtually universal method of healing such an intrusion is for the healing shaman to suck out the projectile and dispose of it, protected from its contamination by a defense made of the same substance.

This phlegm is nurtured by ingesting ayahuasca and the sweet strong jungle tobacco called mapacho. The gateway of this power is the shaman’s mouth, out of which the shaman’s power passes in the form of singing, whistling, whispering, and blowing, especially of tobacco smoke, and into which the shaman sucks out the sickness, the sorcery, the magic darts that cause the patient’s suffering. The maestro ayahuasquero transmits this power to a disciple in unabashedly physical form — a slippery globule passed from mouth to mouth.

In the same way, to learn the secrets of a plant — what sicknesses it can heal, what song will summon it, what medicines it enters into, how it should be prepared — the shaman undergoes la dieta, living in solitude in the jungle, without salt or sugar or sex, ingesting the plant, taking the plant into the body, learning its songs and secrets from within, creating an intimate relationship of love and trust. Solitude, abstinence, the ingestion of the teacher — Amazonian shamans conceptualize this process as learning with the body.

Traditionally, the ayahuasca healing ceremony is conducted by mestizo shamans on Tuesdays and Fridays, late at night, in pitch darkness. Here too the ceremony is a performance of embodiment. For the patient as for the shaman, to drink ayahuasca in ceremony is to be connected to the body in profoundly physical ways.

|

First, ayahuasca tastes awful. It has an oily, bitter taste and viscous consistency that clings to your mouth, with just enough hint of sweetness to make you gag. The taste has been described as being bitter and fetid, like forest rot and bile, like dirty socks and raw sewage, like a toad in a blender. Second, ayahuasca is a powerful purgative and emetic. It makes you vomit, and often induces diarrhea. The vomiting is considered to be cleansing and healing; indeed, ayahuasca is often called la purga and the shaman a purguero. Vomiting shows that the drinker is being cleansed. La purga misma te ensena, they say; vomiting itself teaches you.

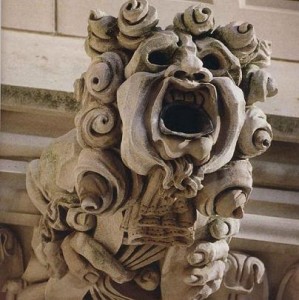

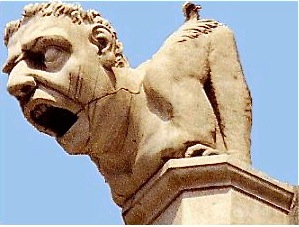

Thus, from the first taste of ayahuasca in ceremony, our relationship with the body is brought into sharp focus. We deliberately ingest something vile; we forcefully eject the contents of our bodies. The body is turned inside out, its boundaries transgressed. We give up control of our bodies, hand ourselves over to the plant, and experience our embodiment in its most primal form. Our body becomes, in the word of literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, grotesque — fully embodied, porous and protuberant, part of the earth, exuberant and fecund.

And then there is the ceremony itself. There are the smells of tobacco smoke and cologne, the one rich and deep, the other high and sweet, like musical tones. There are the sounds of the jungle, the night singing of the frogs, the gagging and vomiting in the room, the whispering, whistling, and singing of the shaman, the susurration of the shaman’s leaf-bundle rattle. Many participants smoke mapacho. Every few seconds the darkness is pierced by the glowing end of a cigarette; as you smoke, the now visible breath enters and leaves your body.

|

At some point the shaman ceases singing and begins making extraordinary and dramatic sounds of belching, sucking, gagging, and spitting. He is drawing up his protective phlegm, to make sure that what he sucks from the body of his patient cannot harm him; then he loudly and vigorously sucks out the affliction, the magic dart, the putrid flesh or stinging insect, the magically projected scorpion or razor blade. He gags audibly at its vicious power and noisily spits it out on the ground.

This is the experience of the ceremony, the shaman at work — a synesthetic cacophony of perfumes, tobacco smoke, whispering, whistling, blowing, singing, sucking, gagging, the insistent shaking of the leaves, the internal turmoil of the purge.

Thus, ayahuasca shamanism is irreducibly physical. The body is the shaman’s instrument of power and relationship — power stored in the chest as phlegm, relationship achieved through ingestion. The shaman learns the plants by taking them into the body, where they teach the songs that leave the body as sound and smoke. An ayahuasca healing session enacts the physical materiality of the human body — nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sucking, gagging, belching, blowing, coughing up, spitting out; sharp sweet smells, rattling, whispering, whistling, blowing, singing, the taste of tobacco and ayahuasca, the imagery and ritual of the body, conflict, mess.

|

Similarly, in the ayahuasca ceremony substances traverse body boundaries, reminding us of our penetrable and leaky borders. Excrement and vomit are ejected, magical darts are sucked out through the skin, internal substances are spit out through the mouth, magical phlegm is transferred from shaman to disciple, tobacco smoke is blown into the body through the crown of the head — the body exaggerated, vast excretions, ferocious corporeality. Reminders of the darker side of human existence constantly lurk in the margins of the shamanic performance — dangerous ambiguity, broken boundaries, ambivalence, transgression, disorder.

All of this makes us westerners nervous. We distrust our bodies. We find vomiting wretched and miserable; we struggle to maintain our body boundaries; above all, we seek ways to evade the ferocious physicality of the ayahuasca experience. When we drink ayahuasca, we focus on visions, insight, transformative experiences. We seek, in the words of psychologist James Hillman, “an imageless white liberation,” a flight from the reality of human embodiment. We secretly believe in what Bakhtin called the bodily canon — the belief that human beings somehow exist outside the hierarchy of the cosmos.

|

I think this is a mistake. I think the healing power of ayahuasca lies precisely in its connection with the earth, the body, with suffering, passion, and mess.

The healing is not conceptual — an insight, a realization, an epiphany. Rather it is a visceral impact on the body. We should not think of ayahuasca shamans as spiritual gurus. What they do has more kinship with eleos and phobos, Aristotle’s pity and terror. That this links to katharsis — cleansing or purging — should come as no surprise. Ayahuasca is, above all, and apart from our own cultural obsession with visions and insight, la purga. The shaman works through the moral themes of healing discourse not linearly but in performance. The grotesque body in fact celebrates the victory of life, its renewal and regeneration, true fearlessness in the face of our ineluctably human condition.

- Previous Post: What Do the Spirits Want from Us?

- Next Post: Thinking About Death I: Heidegger

- More Articles Related to: Ayahuasca, The Medicine Path

In the Minoan tradition a combination of hallucinogens and liquified flesh is drawn off through the mouth of the sacrificed man (or bull) and added to raw honey in order to make the sacred mead. This explains the strange figures found in the European tradition and art

A wonderful article. Thank you!