Explore Articles Filed Under: The Amazon

Jerry Burchfield is a photographer without a camera. Instead, he uses a photographic technique that goes back to the nineteenth-century beginnings of photography — laying materials directly on a black-and-white photosensitive medium, and creating negative images of the shadow cast by sunlight passing through the object. Burchfield calls these lumen or light prints. The results are astonishing.

The term poder verde, green power, was first applied to cumbia amazónica — the boisterous sexy ironic kick-ass garage-band party music that first developed in the Upper Amazon during the oil boom of the 1960s. Now there is an equivalent in painting — an exhibition entitled Poder Verde, Visiones Psicotropicales, Green Power: Psychotropical Visions, which brings together the boisterous sexy ironic kick-ass visionary work of contemporary Upper Amazonian painters.

I have mentioned before that getting clean potable water can be difficult in many parts of the Amazon, including the larger cities. In fact, I strongly recommend against drinking any untreated water in the Amazon, no matter how clear and tempting it might appear. And that includes rainwater, unless you know that the containers in which the water has been caught and stored have been properly cleaned and maintained.

We have talked before about the image of the jungle in the European imagination. Part of that mythology is that the jungle — filled with what German filmmaker Werner Herzog called “fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away” — has a mysterious power to drive Europeans crazy.

In order to become an ayahuasquero, one must be coronado, initiated, usually by receiving the phlegm of one’s own maestro ayahuasquero. Still, a number of mestizo shamans also report being initiated by dreams that announce — or confirm — their healing vocation. My plant teacher doña María Tuesta had such an initiatory dream when she was eighteen, in which the Virgin Mary confirmed doña María’s destiny as a healer. A small detail in the dream is of great interest. The fact that doña María is carried to heaven in her mosquitero, mosquito net, has significant symbolic resonance in the Upper Amazon.

The photograph on the left shows Wilindoro Cacique, original vocalist with the famed Juaneco y su Combo, masters of cumbia amazónica, and Judith Bustos, La Tigresa del Oriente, “making click click,” as one music blog put it — “kissing each other on the mouth like teenagers” and posing very affectionately for the photographers. “Hot-blooded,” said another, enthusiastically.

When Europeans first came to South America, they were awed by the grand civilizations of the Andes. The jungle, on the other hand, was for Europeans a place of dark and savage mystery, inhabited by primitive and ferocious warriors. Two interlocking assumptions about the Amazon have persisted to this day. The first is that the Amazon is a place of virgin wilderness, untouched by human cultivation or management; the second is that the people of the Amazon have always been — as they were found to be by twentieth-century anthropologists — small bands living by gathering, hunting, fishing, and slash-and-burn agriculture.

The first thing I was taught by Gerineldo Moises Chavez, my jungle survival instructor, was how to build a tambo, a jungle hut. It wasn’t fancy, as you can see, but it kept me dry when it rained and kept me off the ground while I slept. In fact, all ribereño houses are built on exactly the same principles — a thatched house on stilts, built entirely of jungle materials, which may range in size from a small temporary hunting shelter, just large enough to sleep one or a few people, to an elaborate structure able to house an extended family.

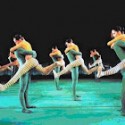

Since we’ve been talking about the Amazon River lately, I thought we might listen to some Amazon River music. The story of this particular piece brings together three significant artists — the dance company Grupo Corpo, the instrumental group Uakti, and composer Philip Glass.

Among mestizo shamans in the Upper Amazon, the verb icarar means to sing or whistle an icaro, a magic song, over a person, object, or preparation, in order to give it power; water over which an icaro has been sung or whistled and tobacco smoke blown, for example, is called agua icarada. Another term for the same process is curar, cure; that which has been sung over is said to be curado, cured, in the sense that fish or cement is cured, ripened, made ready for use.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa