Explore Articles Filed Under: Shamanism

A lucid dream is one in which the dreamer is aware of being in a dream state while the dream is still in progress. Lucid dreams can be extremely vivid and realistic, depending on the level of self-awareness during the dream. Most strikingly, lucid dreamers report being able to actively participate in and often manipulate experiences within the dream environment — that is, deliberately walk, fly, look around, handle objects, and interact with dream persons. Lucid dreams provide a unique opportunity to find out more about the experience of dreaming — and, by extension, perhaps more about the experiences of shamans, and about other visionary experiences, including those related to ayahuasca.

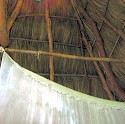

In order to become an ayahuasquero, one must be coronado, initiated, usually by receiving the phlegm of one’s own maestro ayahuasquero. Still, a number of mestizo shamans also report being initiated by dreams that announce — or confirm — their healing vocation. My plant teacher doña María Tuesta had such an initiatory dream when she was eighteen, in which the Virgin Mary confirmed doña María’s destiny as a healer. A small detail in the dream is of great interest. The fact that doña María is carried to heaven in her mosquitero, mosquito net, has significant symbolic resonance in the Upper Amazon.

The Society for the Anthropology of Consciousness and the Association for Transpersonal Psychology jointly present a conference on Bridging Nature and Human Nature at the Edgefield Resort in Portland, Oregon. The conference is intended to create an “interdisciplinary coalition to help reassess science and culture and the interface between technology and nature” — that is, to call for a more systemic, process-oriented, intimate, and sensual understanding of the universe in which we live.

The shaking tent is a ceremony widespread among indigenous peoples of North America, during which a shaman is tightly bound within a darkened lodge, the structure shakes violently, and the shaman — and sometimes the audience as well — converses with spirits who speak and sing, and sometimes appear in various forms, such as darting blue lights. When light is restored, the shaman is revealed to be unbound and sitting comfortably, apparently untied by the spirits.

A story is a metaphysical entity. What exists in the world is the telling of a story. The same story may have different tellings, at different times, by different people, or in slightly variant versions. These tellings are tokens for which the story is the type. We can, arguably, reconstruct a story from its tellings, as we can reconstruct a dead language from its living descendants. But it is the tellings that are alive.

I have always enjoyed reading certain writers — Gabriel García Márquez, Leslie Marmon Silko, Isabel Allende, Italo Calvino — whose works are often grouped together as magical realism. I think I know why. The world of these writers is, in a significant way, the world of the shaman, the visionary world, in which reality is interfused with the miraculous. El realismo magical, lo real maravilloso americano, is deeply associated with the resurgent literature of South America, and is characterized by a detailed realism into which there erupts — in a way often experienced as unremarkable — the magical world of the spirits.

The Natufian culture flourished in the southern Levant between 15,000 and 11,600 years ago. One of the places that Natufian dead were buried is a small cave named Hilazon Tachtit, located on a steep cliff about 500 feet above the Hilazon River, with a sweeping view of the river and the Mediterranean shoreline, in which twenty-eight burials have been excavated. These burials can be dated to between 12,400 and 12,000 years ago, during the time that Natufian culture was in transition from foraging to farming.

Anthropologist Michael Winkelman, at Arizona State University, says that shamanic practices — drumming, chanting, and the ingestion of sacred plants — create a special state of consciousness he calls transpersonal consciousness, and that these practices create this state of consciousness through the process of psychointegration — that is, by integrating a number of otherwise discrete modular brain functions. Anthropologist Homayun Sidky, at Miami University in Ohio, says that this theory, despite a surface plausibility, is without empirical justification.

Among mestizo shamans in the Upper Amazon, the verb icarar means to sing or whistle an icaro, a magic song, over a person, object, or preparation, in order to give it power; water over which an icaro has been sung or whistled and tobacco smoke blown, for example, is called agua icarada. Another term for the same process is curar, cure; that which has been sung over is said to be curado, cured, in the sense that fish or cement is cured, ripened, made ready for use.

I have spoken before about my plant teacher doña María Luisa Tuesta Flores. She was born in September 1940, in the town of Lamas in the province of San Martín, and she died, the victim of sorcery, in July 2006. She had begun her healing career as an oracionista, a prayer healer, and, even after she became an ayahuasquera, her icaros, magic songs, remained inflected with the rhythms and melodies of prayers.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa