Painter Rick Harlow first came to Colombia in 1987 to live along the Caqueta River, near the town of La Pedrera. He spent half his time painting, the other half hunting and fishing with the men of the Yucuna people, “trying to be a productive member of society.” In 1988, toward the end of his stay, he participated in the yurupari, a five-day male initiation rite, involving fasting, drinking ayahuasca, and bathing in cold river water.

|

| Roots (2000). “I really love the elegance and beauty of buttressed roots. In this painting I wanted to focus on the base of just one tree to try and express something of the rainforest.” |

Harlow’s inclusion in this ritual, which is normally closed to outsiders, was controversial among certain elders and came about largely through his friendship with a local shaman. The result, Harlow says, was a “crash course in rainforest education. You learn to walk through the forest without disturbing anything — without breaking a twig or stepping on a plant.”

The ritual ayahuasca experience, he says, “succeeded in breaking down the last barriers between me and nature. I felt my senses opening up. In addition, I was physically exhausted — too tired to worry about what was going to bite me.” His perspective on the rainforest also changed. “It literally taught me a new way of seeing,” he says. “The Indians view plants and animals as entities with human qualities, with whom they have relationships.”

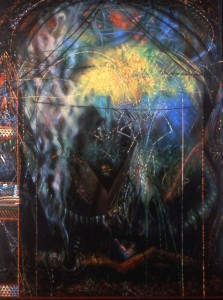

|

| Quantum Mutatus (1989). “Painted after participating in the male initiation ritual of the Yucuna tribe. The imagery comes from visions I experienced under the effects of ayahuasca during a dance on the final night of the ritual.” |

Ayahuasca, Harlow says, “gives you what you need and that depends upon the individual. For me, I got painting lessons.” His artwork, he believes, become deeper, more reflective, more personal. “When my work goes well,” he wrote in his journal, “when I can leave behind any formal precepts about art and simply enjoy an honest outpouring of energy from within myself onto the canvas, nature rings like a bell.”

His paintings, Harlow says, “combine literal and abstract imagery with the aim of getting at different levels of perception. When I am in the rainforest or working on paintings about my experiences, whatever I’m looking at is generally colored by subconscious thoughts and associations superimposed on the scene at hand. Participating in rituals, dances, drinking ayahuasca, getting sick or feeling great all influence my way of expressing how I view things.”

The Yucuna called Harlow the Shaman of Colors, and found his work perplexing. “There are no formal art scholars within the community because, in that culture, art as we know it is superfluous,” Harlow explains. “Indians don’t quite get the idea of art existing outside a special use like decorative baskets or painted masks. Nor can they see why anyone would bother putting paint on a canvas, mounting it on a wall, and selling it.”

|

| Biophilia (1994). “Combines indigenous design motifs with expressions of amorous feelings towards the nature and the energy of life in the rainforest.” |

In 1992, Harlow started a paper-making project with the Yucuna people, largely at their urging, to provide some economic support. “I didn’t want to continue as a tourist,” he explained, “I wanted to contribute to the welfare of the Indians. After some thought paper seemed to be a product with high value relative to its weight. It takes days to transport it by boat to a remote air strip. Because of the shipping costs you couldn’t make a profit with heavy crafts such as ceramics. And paper has relatively high value per kilo of transport.” He learned the craft of making paper and, in partnership with the Yucuna, perfected a recipe using renewable forest resources to produce stationery and other paper handicraft. With the support of the GAIA Foundation, markets were developed on three continents, ranging from international craft fairs to boutique stationers.

|

| Yucuna Maloca (1990). “Late afternoon sun flooding into the maloca at Puerto Guayabo along the Mirití Paraná River.” |

Eventually Harlow was driven away from the village, and from the paper-making project, by FARC, the Revolutionary Forces of Colombia. “They had known of my presence and tolerated it for a number of years,” he said. “But that changed when the US became involved in the battle against them and they wanted all Americans out of the region.”

Harlow is now featured in a documentary film entitled From the Inside Out, by the Dutch filmmaker Jan Willem Meurfens. The two met in the Amazon when Meurfens went there to teach filmmaking to the native people. The footage for the film was shot from over a nine-year period from 1995 to 2004. The voice-over narration is based on a combination of Harlow’s journals and the filmmaker’s use of indigenous mythology — myths of the war between men and fish people, the use of fishnets, the creation of the first waterfalls, the river of abundance, the end of this world.

Harlow’s paintings are complex and haunting. Even at their most photorealistic — look at Yucuna Maloca, above — they capture the magical light and dark of the jungle, its mysterious impenetrable textures.

Much of the material here is taken from two interviews with Harlow — one by Steve Nadis in Audubon , and one by Charles Giuliano in Maverick Arts Magazine. A number of Harlow’s paintings, with brief descriptions, are here.

- Previous Post: Ayahuasca in the Supreme Court

- Next Post: Shaman Superheroes

- More Articles Related to: Books and Art, Shamanism