In 1975 Kenneth Good, a doctoral candidate in cultural anthropology, traveled to the headwaters of the Orinoco in Venezuela to live and study among the Yanomamö. He joined anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon for what was supposed to be fifteen months of fieldwork, funded by a generous grant from the National Science Foundation. But Good would end up living almost full-time with the Yanomamö for more than twelve years, sharing their lives, becoming fluent in their language, and marrying a Yanomamö girl named Yarima.

|

| Yarima in 1992, from the film Yanomami Homecoming |

After Good had been living among the Yanomamö for about two and a half years, he found himself under increasing pressure to become betrothed. The headman of the village was insistent. “I found myself thinking that maybe being married down here wouldn’t be so horrendous after all,” Good writes. “Certainly it would be in accordance with their customs.” The more he thought about the idea, the more attractive it became. “After all, what better affirmation could there be of my integration with the Hasupuweteri?”

It is common among the Yanomamö for an older man to become betrothed to a younger girl. Such betrothals are not consummated for some time — perhaps not ever. The Yanomamö understand that sometimes these relationships don’t work out. A girl might thus be betrothed several times before actually being married. The girl brings food from her mother’s fire to feed the man; he brings her his own gifts of food. They talk and joke together. Eventually, the girl feels comfortable being around his hearth and being around him. If things work out, they become friends.

When the girl has her first menses, the man and his betrothed hang their hammocks side by side, and they have sex for the first time. The girl thus has an instant husband and protector. Women beyond the age of puberty are routinely raped if they do not have husbands.

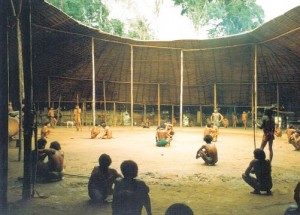

The Yanomamö have nothing like a formal ceremony comparable to marriage in American culture. Divorce is just as informal. The departing spouse simply removes his or her hammock from the space of the other spouse inside the shabono, the large communal house, and then resists or refuses reconciliation and reunification.

Good figured that the betrothal would not last, and presumably would never be comsummated. He was, after all, going to go home at some point. But he thought, “What the hell, what would be so wrong in saying yes?” So he agreed. “Good,” said the headman, smiling broadly.“Take Yarima. You like her. She’s your wife.”

At that time, Yarima was around nine years old. Good was thirty-four.

|

| Valdir Cruz, Yarima (1996) |

Good found himself becoming increasingly fond of his child bride. The community began taking it more seriously too. The women started calling Good yarima heorope. “Our relationship changed,” he writes. “Before, Yarima had been the cute little girl with the smile and the hello. Now it was something more than that and, as time passed, a good deal more than that.” Yurima had her first menses while Good was away on a long trip. When he returned, they hung their hammocks side by side, and they consummated their marriage.

Yanomamö do not keep track of their age. Good and Yarima were married shortly after Yarima’s first menstrual period. In a nonindustrial society, especially one like the Yanomamö, where obesity is virtually unknown, a girl would normally have her first menstrual period between the ages of thirteen and sixteen, much later than girls in industrial societies. A good guess is that the marriage was consummated when Yarima was about fourteen years old. Good was by then close to forty.

The marriage created problems in the village where Good lived with Yarima. Yanomamö attitudes toward women and sex were very different from his own, and, while he might normally regard these with anthropological detachment, his attitude was different when they were directed at Yarima. Good frequently had to be away from the village — for permits, visas, research funding. He made a public and very angry announcement that his wife was to be left alone while he was gone. Still, on one occasion when he went downriver on business, the village decided that he was dead, and Yarima was raped by a number of men. One of the men was his own brother-in-law, Yarima’s sister’s husband, with whom it was considered normal for Yarima to have sex. But Good was furious when he returned, and he berated the man publicly. Another time when he was gone, Yarima was beaten and her ear partly ripped off. Yarima’s brother could not understand why Good was so upset by all this. It’s just naka, he told Good, just pussy. What do you care?

These difficulties were eroding his relationships within the village. And now, too, Yarima was pregnant. Finally, in 1987, after living with the Yanomamö for twelve years, Good took his nineteen-year-old wife and went back to the United States. The couple moved in with Good’s parents in Media, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. Here they were married in a civil ceremony, and here their first child, David, was born.

|

| A Yanomamö shabono |

The following year, in 1988, they returned to the jungle for a visit, taking David with them. Yarima was pregnant again, and, while they were there, Yarima gave birth to Vanessa, their second child. The visit cost Good about $23,000 for supplies, provisions, air fare to Venezuela, the flight to the interior, and the five- or six-day boat ride up the Orinoco River to Yanomamö country. If they were going to keep visiting Yarima’s people, Good would have to make some money.

In 1991, Good, along with author David Chanoff, wrote a book about his experiences among the Yanomamö entitled Into the Heart: One Man’s Pursuit of Love and Knowledge among the Yanomama. The book also contained bitter criticism of Good’s one-time mentor, Napoleon Chagnon. It was a moderate popular success, and it continues to be frequently cited in discussions of Yanomamö culture. It also made the couple, briefly, international media celebrities. Good sold their story to Columbia Pictures for $50,000, and he says that he received a telephone call from actor Richard Gere, who was interested in playing him. The money helped Good finish up his doctorate — not under Chagnon, but under well-known anthropologist Marvin Harris at the University of Florida.

At about this time, author Ron Arias interviewed Good and Yarima at Good’s parents’ home. All the questions were passed through Good, who translated them into Yanomamö. “The Yanomamo live naked their whole lives,” Good told the interviewer. “When I first took her out of the jungle, it was a constant struggle to get her to keep her clothes on. If I turned my back on her or left her alone, off they’d come. One time I had to chase her down the street to cover her up.” Arias heard stories of how Yarima thought that automobiles were going to bite her, how she learned to make light by moving a little stick on the wall, how she had given up her hammock to sleep on a big soft box. Once slender, she was now short and stocky. “I see no joy in her face,” Arias wrote, “and I’m feeling uneasy because we’re talking about her as if she were an object or pet from another time.”

|

| Inside the shabono |

Finally, in 1992, Good found a job teaching anthropology at Jersey City State College — now called New Jersey City University — in Jersey City, New Jersey. NJCU is a small urban public commuter school, which began as a state teachers college and officially became a university only in 1998. The school has no department of anthropology, and until 2008 Good was the only anthropologist on the campus. It is not clear to me how Good wound up teaching at this school. He had his doctorate; he had worked for the prestigious Max Planck Institute in Germany; he had extensive — indeed, extraordinary — field experience; and he had published a significant memoir. Perhaps he was, at the age of forty-nine, considered too old for other entry-level positions. He had also quite publicly broken with the powerful Chagnon. Apparently Good was having trouble getting academic employment, and he and his wife found themselves in a small apartment in Rutherford, New Jersey.

The couple continued to attract media attention. Reporters were obsessed with Yarima’s exoticism, and made constant references to her alleged Stone Age origins, as if the Yanomamö somehow had no history. One reporter described the Yanamamö as “naked Indians who feast on termites and tarantulas and have yet to invent the wheel.” Another said that “modern devices such as washing machines, television and the telephone were as foreign to her as they would have been to Neanderthal man.” The same writer quoted Yarima’s English language teacher as saying that Yarima was four feet tall and had no concept of time. “She did not know if it was morning or afternoon,” the teacher told the interviewer. And she added, “One thing you noticed about her was that she could not coordinate colors.”

Yarima had grown up in a shabono, surrounded by people. Her day had been spent gathering fruit and fishing with her sisters and mother. They would make a fire, sit and talk, laugh, watch each other’s babies and take turns going off to gather food. Then they would go to the stream, wash their babies and themselves, and come home with flowers in their hair. In New Jersey, she lived in a small apartment — isolated, alienated, and bored. Running water, appliances, malls, and television were not enough. She spent the day listening to cassette tapes Good had recorded of Yanamamö voices and the sounds of the jungle, and watching the videos they had shot on their 1988 visit. One interviewer noted that Yarima did not leave the house unless Good went with her. They had no friends among their neighbors, whose houses were abandoned by working husbands and wives during the day.

|

| Valdir Cruz, Yarima Breastfeeding Among Her People, Venezuela (1997) |

Good also notes that Yarima began to view him differently once they were immersed in his culture rather than hers. He did not carry a shotgun. He obeyed the orders of police officers. When, after a minor traffic accident, a woman yelled at him and called him an idiot, he did not shout back and threaten her. Yarima thought he had lost his manhood.

And now Yarima had a third child, Daniel, to take care of. She did not understand why Good did not spend more time at home with his children, as Yanomamö fathers do, or why he had to leave her alone in the apartment every day while he went to work. “She didn’t understand meetings,” Good told an interviewer, “time periods, schedules, students sitting in class waiting for you, why I had to go every day.” Once, on a book tour together, to her dismay, Good said he was too busy to talk with his daughter on the telephone. Good dismissed her concern. “She can’t understand how it is I don’t want to talk to my own kids,” he said, his hands on her shoulders. “She’ll get Americanized.”

Both Good and Yarima thought it would be a good idea to visit her home village once more, but they could not afford the trip on his salary as an assistant professor. Finally, in 1992, National Geographic agreed to finance the trip if they could make a documentary film out of it, to be called Yanomami Homecoming. The magazine sent three boats full of people and equipment to the Upper Orinoco, but not — as they had apparently promised — either a doctor or medical supplies for the Yanomamö. The National Geographic filming, too, seems to have been something of a disaster, which was in turn captured on tape by a village Yanomamö who had acquired his own 8mm video camera.

While Good and Yarima were awaiting the film crew in Caracas, Good learned that his father had died, but decided to honor his commitments to the film crew rather than return to the United States. Yarima could not understand this; Yanomamö have very strict rules about obligations owed to deceased relatives. When she returned to her village, Yarima learned that her own mother had died, and her own intense grief only underscored what she perceived to be her husband’s callousness. Moreover, according to Good, members of the film crew, presumably in order to make more dramatic footage, encouraged Yarima to criticize him.

|

| Valdir Cruz, Yarima and Son, Venezuela (1996) |

Finally, Yarima simply ran away, apparently at the instigation of a member of the National Geographic film crew. This happened at the airstrip in Platanal, just as they were about to board the plane for a flight to Caracas. Good and Yarima had spent days in agonizing discussion about her wish to remain with her people, and she had agreed to give New Jersey one more chance. But she changed her mind at the last minute. She stopped, hesitated, and then just turned around and left.

For a while, Yarima appeared on talk shows in Caracas, discussing her decision to abandon the United States and her family. Then, at the end of 1993, she disappeared into the jungle. There were rumors that she was dead, or hiding in the hills.

In 1996, investigative reporter Patrick Tierney, accompanied by Brazilian photographer Valdir Cruz, while doing the research among the Yanomamö that would result in his scathing and controversial book Darkness in El Dorado, had his sleeve tugged by a woman who said, in perfectly good English, “Hello. My name is Yarima. What is your name?”

Tierney writes that Yarima was nursing a baby and looked, as he put it, radiantly healthy. She had married again, Cruz says, and had two more children. She told Tierney that her new husband was treating her well. She asked about her three children in New Jersey, adding, “Here good. Jersey bad.”

Tierney’s discovery of Yarima among the Yanomamö became as much of a news story as had been her life in New Jersey.The Times of London published three stories in 1997 about how Yarima had abandoned civilization for the jungle, and about a new expedition that would entice her back by playing tape recordings of her three children in the United States begging her to return. The expedition turned out to be nonexistent.

That is as much as I know. I have seen no additional reports of Yarima’s life in the jungle. Good and Yarima are divorced, and he continues to teach anthropology at New Jersey City University, where his students consider him a likeable if undemanding teacher, and enjoy his stories of life among the Yanomamö. A proposed sequel to Into the Heart has not appeared. I do not know if he has remarried. Yarima, if she is alive, would be around forty-one years old. Good and Yarima have not seen each other for sixteen years.

- Previous Post: Sex and Violence in Amazonia

- Next Post: Sacred Mushrooms of Mexico

- More Articles Related to: Books and Art, Indigenous Culture, The Amazon

Interesting story, Steve. I read Good’s book soon after it came out in 1991, and have occasionally wondered what became of them. I suppose this is as much as anyone will ever know. Even if this is an extreme situation, this tale brings up questions regarding the extent to which inculturation in a society other than one’s “own” is possible. It is no secret that I have thought about this quite a bit…

I’m a little late to the conversation, but in my opinion, enculturation can take place to the extent the person is willing to be enculturated. It sounds as if Yarima was taken to the U.S. largely against her will, or at least without understanding entirely what was going to happen, and had no real desire to stay. She understandably missed her family and everything that was familiar, plus she was ridiculed and likely treated like a child or a circus freak. She had no friends and her husband turned into a completely different person than she’d known at home. So, long reply for a short answer..I’m not sure if complete enculturation is ever possible, as we all have biases and ways of seeing things, but I do think, as I said before, that enculturation is possible to the point a person is willing to be enculturated.

Here is a link with the complete history (spanish) http://www.bbc.co.uk/mundo/noticias/2013/09/130903_en_busca_de_yarima_yanomami_amazonas_vp.shtml

I know this history since I saw the National Geographic program on Venezuelan TV 15 years ago, I make my first internet buy on Amazon books 8 years ago to buy the Kenneth Good book because I saw a rerun of “Yanomami homecoming” on Radio Caracas TV and I keep thinking the National Geographic’s story is too ethnocentric so I NEED to know the story from another point of view. I read the book on a night (I don’t sleep that night) and since then I has been obsessed by this tale (and the opportunity of discuss tolerance of different points of view) and by the desire to tell the tale from Yarima’s standpoint to show some of current occidental culture characteristics that only can be analyzed from a foreign standpoint. I has dedicated countless hours to research on Internet about Yarima and Kenneth Good over the years, and this is the more balanced summary I had read on the net about the subject. It is too the more updated report and has some inside information that I had not read on any other source. So congratulations for a great article, very informative and made with passion for the respect to the view of others. (Sorry by my poor English, I speak Spanish and my English is the learned at high school and reading English texts).

I should clarify that the crew of National Geographic documentary was hired.(the Venezuelan team of famous Radio Caracas Televisión program “Expedición” ) because they had the experience and logistics to film in Yanomami communities. I suppose that an accord was reached to give the Venezuelan broadcast rights of the documentary to RCTV in exchange for the teams work. This is the only “Expedición” program (in Spanish) that cannot be obtained in video and to obtain the program (in English) you has to go to National Geographic.

Really it was an interesting anthropological love story. I did not much about Yanomama tribe before I gone through that book. I collected a copy of Kenneth Good’s book from a street vendor in the New York City in 2001 and finished reading the whole book during my short stay around NYC. It must be a very normal situation to get conflict while staying long period and building close relationship with such local people in the deep Amazon. But I was confused why Mr. Napoleon Chagnon got angry about the relationship (as he was an anthropologist) and showed his bad temper on Good’s doctoral degree.

You are confused as to why Good’s mentor had a problem with his 34 year old student marrying a 9 year old?

If a 34 year old woman had married a 9 year old boy, would this also not be a problem for you?

In what culture is this considered acceptable?

I enjoyed your thorough and balanced account of this unusual story. Thanks especially for linking to the other articles. I do not romanticize what Good did. The issue for me is informed consent. Did Yarima have the ability to understand where she was going and agree to it? Obviously not. What Good did seems racist and paternalistic to me, assuming he was the best judge of what her future should be. Cruel to her, and unimaginably cruel to their children who are now motherless

In Professor Good’s book “Into The Heart” (page 121) Good wrote: “And now, suddenly, out of the clear blue sky, I had a Yanomama “wife” — a wife of sorts, anyway. And not only a wife, but Yarima no less, who couldn’t be more than twelve years old.”

Professor Good’s students, at New Jersey City University, are taught that anthropologists can become sexually-involved with their child research subjects — without violating the American Anthropology Association’s Code of Ethics.

Because I was the only faculty member, at NJCU, who objected to Dr. Good’s “romance” — NJCU arranged for Dr. Good to file a “Civil Rights” complaint against me, with the New Jersey Attorney General.

This on-going investigation is now in its third year — and recently (August 2010) this “Civil Rights Violation” complaint was moved to the Office of New Jersey Governor, Chris Christie.

If you find this to be a misuse of the police power of the state, and an assault on academic freedom, please call Governor Christie (609-292-6000)

Good is now promoting “Into The Heart” (which he sells to his NJCU students, in violation of New Jersey law) on-line. Google: “Images for Kenneth Good” and, make sure the “safesearch” is checked “off.” Then (about ten photographs from the first in the series) select the photograph of Professor Good accompanied by his totally-nude, 12-year-old wife.”

Good treated his wife like a circus elephant — and used her up for promotional purposes, then shipped her back to the jungle — without her kids.

What’a guy — what’a role model for NJCU’s anthropology students.

Google: “Fraud at New Jersey City University” for more involved with this story.

What a sore and jealous man you are Dusenberry.

I took Dr. Good’s class and found it interesting and inspiring; gave me a glimpse of what lives some people live.

You, on the other hand, have a really bad rap among the students. Read your ratings here: http://www.ratemyprofessors.com/ShowRatings.jsp?tid=326718&page=1

You need to stop being envious of Dr. Good’s life and try to make yours better. Start by making your classes interesting and actually teach something.

I befriended Yarima while living in the same apartment complex in Gainesville, Florida. David and Vanessa were small and precious. In the year i was there (89-90) i have to agree with this previous person. Ken Good spent no time with Yarima and was always trying to pawn her off with other people. She also conveyed to me that Ken Good had been violent with David for jumping on the bed and it had really upset her. I felt great empathy for Yarima she had no place in this western culture and i would not have called it a love story by any means.

I have often wondered about Yarima, David and Vanessa and what became of them. I hope Yarima is at peace and that her children will come to understand with compassion why Yarima chose to stay in Venezula, she loved them so much.

So a 34 year old man marries a 9 year primitive woman, consummates the marriage when she is 14 years old and there are people here who have no problem with that?

I suppose those are the same people, mostly men, it appears, who have no problem with child brides in Afghanistan either, because us Westernerners are so uptight about pedophilia, ya know?

I’m sorry to say this, but a 34 year-old man getting married to a 9 year-old is no different than the same man getting married to a 20 year-old; Why? Because in no way does the definition of ‘marriage’ say, “A union between an older man above the age of 20 and a woman of the same age.” Their culture is their own! Just because American culture believes that only “mature” individuals can get married does not mean that they have to change their own ways of life to assert to ours. In reality, they are the ones living a full, simple life. They go out to get things done, we on the other hand live in a world of fast, quick results and strict morals of what a person should be and what they shouldn’t do. I find your beliefs on their cultures so called wrongs hideous. This is how they’ve live for many years, you may call them primitive but all that means is that they don’t have the modern conveniences that we have. Our culture contains Christians forcing others that they call primitive men (Not that all Christians are bad.) to “Liberate people from hell for their devilish crimes,” We have fast-food restaurants and life-styles that lead to obesity and early death. Do they have that? No. They are perfectly fine they way they are. Honestly, people like you are no importance to me, you’re just as insolent as that Dusenbury guy.

Professor Dusenberry’s account of the dispute is here. He argues that it is inexcusable — and, he says, racist — “that the American Anthropological Association has no formal policy against sexual involvement between its members and third-world children. The American Sociological Association has such prohibitions, and so does the American Psychological Association.” He considers Good’s marriage to Yarima to have been the sexual exploitation of a third-world child, and that NJCU, by hiring him, at least in part on the basis of his published memoir, has endorsed this exploitation. I would be very interested in hearing any additional thoughts on this issue.

That is an accurate description of what happened and anyone who does not see that the balance of power is not equal between a 9 year old child and a 34 year old man in *any* culture, much less where the child is from a primitive society, is truly delusional.

I find it astounding that any university would hire an admitted pedophile and am amazed that any student would look up to him, much less respect him, as if Good being an anthropologist somehow made him subject to different rules than a child molester visiting Thailand. Because this means if they write a book about the experience, that makes it okay, then?

Why must marriage partners have equal power? Why is that a good thing? When partners have equal power that leads to constant power struggles and unhappiness. Many females are happy to marry males who are more powerful than they are. Many females are happy to serve their male partner. Most American women today are lonely and unhappy. They have power, but that is all they have. They do not have love. They made a bad trade. It is bad enough the feminists made modern and women unhappy. Now they want to force their unhappiness on other civilizations. Everyone today wants to be things they are not.

William Dusenberry accuses Good and the American Association of Anthropology of “racism,” all the while he calls post-pubescent individuals in Latin America “third-world children.” Doesn’t get more arrogant and racist than than, in my opinion. He also thinks that each person in the world is bound to the norms of her or his own culture, and thus, cannot think for her- or himself. Not everyone is such an unthinking dote as you Dusenberry. In the U.S., the “norm” for many is to dump your aging parents in an institution (euphemistically called a “nursing home” all because folks don’t want to care for their own parents. Does that mean we’re all required to conform to such inhumane practices? A third point is in the U.S., in 22 states, 14 year olds can get married with a judge’s approval, and in all 50 states, 16 year old “children” can get married with their parents’ approval. In most of the world, post-pubescent individuals are considered old enough to marry. Stop being an arrogant racist American, Dusenberry, by imposing your mainstream American values on everyone else. Last, Dusenberry is so concerned about Good “exploiting” his students because he receives money from them from his book. Dusenberry, stop receiving your paycheck from the university you work for! You’re explointing your students who must pay your salary in the form of tuition and the taxes they pay. You hypocrite. So obvious you are jealous of Good (in addition to being an unthinking racist American).

Ah yes, here comes a woman defending a 34 year old man marrying a 9 year old girl, because it is within their ‘values’ and all values are equal. Child brides in Afghanistan? No problen. Clitorectomy, just cultural. Stoning women for showing an ankle, we mustn’t judge.

How very despicable to even think that way, much less write those words.

I interviewed Ken Good and Yarima in 1987 for People magazine, a story with a central figure (Yarima) that has stayed with me as a microcosmic version of what white western man generally has done to the indigenous natives since contact began centuries ago, bringing about change and near extermination. But in this case there’s what appears to be a happy ending, at least for Yarima. I’m glad for her and her new family.

As for Good, he’s still employed and keeps his Yanomamo connection through his three children with Yarima. “A Love Story” doesn’t indicate what the children, now grown, are up to, but I hope they someday reconnect with their mother.

I saw this on National Geographic and became very intrigued with the story. I search for more information and finally stumbled upon this site. I am really curious to know how the kids are doing. Am pretty sure they are adjusting to the modern world really well. This story really opened my eyes regarding on how sometimes we loved to convinced people what is good for them, like modernization and civilization. But in actual fact it might not necessarily be a good thing for them. Living peacefully in the jungle might not seem a bad idea compared to us living in a rat race world.

I’m from South East Asia. I stumbled upon this article when reading about child brides. With due respect, I agree with Ron Arias about the ‘white man’, change and acculturation of indigenous natives.

Obviously, Yarima was ill-prepared for such a cultural shock, being ‘yanked’ out of her homeland to America. And with all due respect to Asst. Prof. Good, I don’t think it was right for him to marry a child bride, uproot her out of her homeland with little preparation for her life in the United States. Being Asian myself, and being born in Borneo (where we have a similar tribe called the Penan), I do find it rather offensive that he never taught her English before bringing her to the United States and leaving her to live in a ‘cubicle (compared to the jungle)’ all by herself.

I would not entirely discount Mr. Dusenberry’s claim that it was for monetary gain, although that might have been said out of jealousy. However, being a woman, I DO agree with what Mr. Dusenberry said that there should not be any sexual involvement between anthropologists and (third-world) children. Third world being in parenthesis because he would never be able to marry a 9-year-old bride in any developed country, without being legally persecuted. Although, coming from a ‘third-world’ country myself, I do agree that sometimes child marriage is the only way out of poverty, I find it extremely offensive that someone from a country that is supposedly more developed in almost every sense would use anthropology as an excuse to indulge in a child marriage.

In most countries, including, currently, some ‘third-world’ countries, it is legally an offense to marry child brides. Rightly so. There are many repercussions to child marriages. It may be the lesser of two evils (hoping, at least that the child bride would not starve to death, etc.) but being the lesser of two evils does not make it right. Many child brides die in childbirth because their bodies are biologically ill-prepared for motherhood.

I am glad that this article is more balanced than some I’ve read, but in my personal opinion, Kenneth Good should NOT have agreed/ asked to marry Yarima (depending on the version of events and/ or reports/ interviews), and taken her out of the jungle completely unprepared. I think both actions were extremely irresponsible and disappointing, coming from a world-class anthropologist. He should have known better. I hope no other anthropologists would ever do the same.

Just as the study of psychology has progressed in terms of ethics regarding test subjects and experiments, I hope the study of anthropology would as well.

If she had not married Professor Good, she would have married someone else. Humans evolved to start having children from puberty. Once a human reaches puberty they are no longer a child, they are a young adult. The extended adolescence we have today is a recent invention. Marriage and childbirth following puberty was common until 150(?) years ago.

I do believe it was unfair of Professor Good to leave his wife alone. He probably should have allowed her take another Yanomami husband, and chose to live in rural area where there was a lot of nature. I am willing to bet she would have adapted to an environment like that.

In fact, I believe we have a moral obligation to provide these civilizations with items that would benefit them.

I would hope if some alien civilization from outer space discovered our existence, they would help us. I think it is unconscionable that we don’t offer these primitive civilizations help and a little guidance. When I speak of guidance, I don’t mean changing their customs or lifestyle, I mean helping them achieve peace with their neighbouring tribes and working together with their neighbouring tribes.

And we should be able to offer them medical treatment. We should treat them the way we would want to be treated if we were in their situation, and they are in our situation. How I hate modern man who care so little about their fellow man.

These people live the way they do because they don’t know any better. I don’t mean in terms of not wearing clothes or practicing their beliefs. I mean in terms of fighting other tribes, not have access to modern medical care, and not having access to some very basic technology like water purification, the ability to make fire, etc. We could help them in little ways that would make their lives much easier. We should share a tiny bit of our powerful “magic” with them. I think that is part of the reason Yarima Heorope went back. I think she wants to help her people. They are our people, too. We can do better than “benign neglect.”

What a very interesting love story. It only proves that sometimes love doesn’t work out fine because of cultural differences. I hope Good and Yarima are happy and fine in their life.

Dear Readers,

Thank you, Steve, for this article. I believe it was one of the better ones I found on the internet. There are some things here and there that are slightly, but innocently, misconstrued. However, I greatly appreciate your summation of the story involving my father and mother.

I’m not here to directly engage in or rebut any individual’s blogs or opinions. I appreciate all of your concerns and comments. I realize how hard it is to make an unbiased opinion using cultural relativism. So commonly people discredit the Yanomami culture as if it is negligible, null, and void. I also understand that no one will ever know all the details of my family’s history. One can only make inferences based on limited facts, rumors and personal life experiences. But I appreciate them anyway since it shows that this subject is important enough for someone to write about and openly discuss. I would like to send out some updates and make a few points:

I’m currently in the Amazon and have reunited with my mother after 19 years of being apart from her. She’s healthy and as beautiful as ever. Yarima and the rest of my Yanomami family are building a new home closer to the river so that they can obtain, more easily, modern goods (machetes, fish hooks, fish line, axes, and medicine). Things they need for survival. Though there is a cultural barrier between my mother and me, it did not stop us from expressing our love for each other nor did it dissolve the bond a mother has for her child. It was a beautiful moment for the both of us.

I’m 24 years old and just graduated with my Bachelor’s in Biology. I battled life growing up without my mother, but I understand now why she had to go back home. When she was here in modern civilization she did her very best to adapt and learn English. My father did all that he could to ameliorate the effects of culture shock. My mother and father loved each other immensely and the decision for them to start a life in America was a decision made as a couple; a couple that battled all odds with the support of each other. I have many memories of my mother (going to malls, riding the rollercoasters, attending festivals and fairs, dancing to music, wrestling playfully with my father, on and on) and we were a happy family. Unfortunately, the unrelenting, aching despondence she felt being apart from her Amazonian life and family forced her to go back home. This I completely understand.

My father loved and cared so much for the Yanomami. He spent years and years with them. And after I’ve spent some time with them I know why he did. After all these years, the Yanomami came up to me and told me, straight from their mouths, their absolute gratitude for all that my father has done for them. They consider him a brother, a father, a son, and a friend.

While I’m sure such discussions as this will continue on forever, I look forward to focusing on the contemporary issues surrounding the Yanomami. There are many good people here fighting with blood, sweat, and tears for the Yanomami, my family. They want to better their lives and it is their human right to do so.

I want to thank you all for your input, comments, remarks, criticisms, diatribes and praises. I welcome them all. I am proud to be a Yanomami-American and connecting with my indigenous roots has been a life changing event.

I want the world to know, understand, and embrace the humanness of the Yanomami irrespective of the radically different lifestyle. Because when we do, the better and more accurate we can relate to them as fellow human beings. And that is my goal.

Best wishes to you all,

David Good

Wow… this is amazing! I have been searching for this information for years! I watched “Yanomami Homecoming” more than a decade ago on TV. The last line of the program, which said that Yarima had chosen to stay in the Amazon while her husband and children returned to the USA, was heartbreaking but not at all surprising considering the overwhelming cultural losses that she must have experienced in leaving her people to join our crazy (and isolated) lifestyle. Ever since I watched that documentary, I have been haunted by questions about what became of Yarima, and how her former husband and children were faring without her.

I have done several web searches, but not until today did I finally find this excellent update… and the surprising comment by David Good.

Thank you so much, Steve Beyer, and thank YOU, David Good for taking the time to share your wonderful story with us. You didn’t owe it to us, but I certainly do appreciate it!

To David

My mother recently passed away and as I am cleaning out the house I came across an old article she had on your parents as your father is her 2nd cousin and I am not sure who sent this to her. I do remember her sharing it with me but never thought to look up any further information at the time. I have become more nostalgic as my children grow and my son is looking to work on a family tree. Our family is so small and I know when I was quite young I met your father but had to have been more than 50 yrs ago! My grandmother was Linda Caldwell and your great grandmother must have been either Silvia or Madeleine. I am going to track down your father’s book as my interest is certainly piqued and hope your family is well. Warm regards, Diane Urbanek

Dear David,

Tonight, my daughter asked me for the “Yanomami Homecoming” video I purchased long ago. Then we all (she and her husband, my wife and I) decided to watch the extremely well done documentary. Many years ago I exchanged meaningful correspondence with your father after reading his book. Now, time lapsed and you are a full grown man with a gifted mind. I appreciate very much your writing. Please, say Hello to Ken and your brothers. My best wishes to your Mom and her new family. You can see some of my efforts on Facebook where I have some of my projects including a page on .

I would like to keep in touch with all of you. Right now I am in the USA but my home is in Venezuela.

Love to you all,

Hector Perez Marchelli

a page on… Rionegro, Amazonas, Venezuela.

hello My name is Marc. Live in Belgium . I read the book years ago from Kenneth Good .Can somebody tell me if Yarima had contact with her children or did they travelled to Venezuela. ??

I was a student in 1992 at Jersey City State College and took Professor Good’s Anthropolgy class. It was one of the most interesting classes I have ever been in.

Fascinating reading.

David, thank you so very much for the update on your mother. Please know that your parents story touched so many people and please do keep us updated further if you have the time.

A word about the National Geographic documentary….

I recollect seeing this originally on PBS in the 1990’s at a running time of 90 minutes.

So amazed was I by this documentary, I kept an eye out for further re-broadcasts of it and it did indeed re-air several months later but at a reduced running time of only 60 minutes. Among the 30 minutes of missing footage was details pertaining to Yarimas young age at the time of her betrothel to Ken and the betrothel practices of young girls in the Yanomami culture.

The trimming down of the original documentary was a travesty.

Perhaps this footage was cut as a result of pursuing ‘political correctness’ at the expense of truth.

This was not only a beautiful documentary before it was butchered, but also a beautiful real life story. There was nothing obscene or inappropriate in the now-missing footage and it should be restored.

If anyone knows where to obtain a copy of the complete and uncensored version of the documentary, please kindly share this information.

Again than you to all for this discussion.

I come late to the party too, but the fact that he didn’t want to speak to his daughter on the phone and that he chose to stay on the expedition as opposed to going home and tending to his father’s funeral, were as appalling to me as it seemed to be to Yarima. As a latina, family is all important. He just was too cold for her. I’m glad she got to go back to her familia.

It’s 2013 and the Yanomami still are in the “international news”. In 2012, an ambush attack of some Yanomamis on others, was quickly turned into an international sensation by Britain’s NGO “Survival International” with the claim that “Brazilian gold miners had killed an entire Yanomami village” located in Venezuela. Then, “Survival International” was forced to retract: No Yanomami was killed and no village had been attacked. It all had been caused by one Yanomami who calculated that the news would cause overflight by military helicopters – which would scare the Yanomamis involved in the ambush. There are THOUSANDS of NGOs of the USA, Britain, Germany (mostly “indirectly” government funded) active in South America – sabotaging the INCLUSION (not integration) of indigenous ethnicities with national society. South American governments observe the “foreign NGOs” as primarily serving geopolitical aims to “control” their nations, prevent their development projects and instigate frictions between different races and ethnic groups. Thus – the age of “anthropoly” is over, and a “soft geopolitical war” is raging in South America, between the national governments and the U.S. Britain and Germany whose NGOs have the primary aim to disrupt development, independence and national unity.The aim is to prepare for NATO “protection” of indigenous autonomies, and for NATO expansion into the South Atlantic But South American goverments can only watch for the time being, and not terminate the “foreign NGOs” – as INDIA did in 2012, when it prohibited transfer of funds from the U.S. and Europe to 4,141 of their NGOs which have been investigated for “activities against the national interests of India”. For references see CONVERSA AFIADA ABIN ONGS,- -Video: PROFECIA ORLANDO VILLAS BOAS. About NATO expansion: FUNDACAO KONRAD ADENAUER PUBLICACAO CONFERENCIA SEGURANCA FORTE COPACANA 2010 (also for 2011, 2012 – U.S. plan code “Cut the Atlantic-divide”).

Jan (Z. Volens), any more info/sources on your claims? Thanking you in advance ..

Well, that is a mystery solved. Thank you David, and best wishes to you and all your family. I loved the original book, Into the Heart.

My late mother, bless her, told me when I was maybe 15 that sophistication in a girl was not a compliment; likewise I think Yarima would have found our sophisticated world quite unnatural, even depraved.

Kenneth Good’s son David returned to the Amazon to reunite with his mother. BBC and other outlets have articles about his experiences:

Return to the Amazon to find my mum

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p018qzzp

ESU grad David Good has one foot in the 21st century and the other in the Stone Age

http://www.poconorecord.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20120409/FEATURES/204090304

My Amazonian Adventure: A Yanomami Reunion

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpP7GR12dtc

William Kremer’s article on BBC website of David Good’s visit to the Amazon:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-23758087

I found your article after reading about David Good attempting to find his mother twenty years after she left them. Here is the BBC article:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-23758087

Their son David Good has begun a beautiful journey, called the Good Project, likely to rediscover and heal this story of his life. We can be careful having too many opinions about another’s life, it is theirs, after all.

Here is a video of his touching reunion with his mother:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpP7GR12dtc

So much has happened since then for David, including the birth of something called the Good Project. He seems like a warm and intelligent young man, finding his way. Check it out here:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Good-Project/375077895861211

David,

I remember meeting you, your sister Vanessa, and your mom probably 20 years ago. My mom is one of your Aunt Anne’s sister. I have been looking for info o how you all were doing over the years, and finally I found something of value on this site. Your story is an amazing one, and I’m glad to hear you are doing well, and I hope the same goes for your sister, brother and father. Best wishes!

Our civilization has acomplished some priceless advantages–science, technology, education and our hard-won precious democracy. But we need to go back, take a another look at history and see what we have lost. Our civilization (especially the European conquest and ethnic cleansing of the Earth) has wiped out and lost our basic and essential human pattern–the SMALL, LOVING COMMUNITY, the grouping system we evolved to live in and did live in for millions of years before it was wiped out by our civilization. Our civilization wiped out the small, loving emotionally-bonded community and unwittingly left us living isolated and alone in dysfunctional, cold, uncaring, mass society, Thus, today we are a group animal without a group. Today, we live disconnected in non-caring, non-communities. The behavioral toll in

anxiety, depression and unhappiness is catastrophic. Most people may not realize we are not genetically programmed to live the way we live today. One might think we are ordained to live this way, because none of us were born before our grouping system was destroyed. Only someone like Yarima who has experienced both worlds, and though uneducated, knows the overwhelming difference. Loved this story and hope we, through science, can learn what Yurima knows and give OUR culture a makeover. I am especially interested in this issue,

and am trying to come up with a system which will allow us to return to our genetically

predetermined grouping system–the SMALL, loving, bonded community. If you have any

ideas, please share them with me.

turningpoint10@ymail.com . .

I too heard this story twenty or so years ago. I always wondered what happened to Yarima. And I wondered what would become of her children. Never in my wildest imagination did I think things would turnout so well for all involved.

The same goes for me. For years I had been wondering how Yarima had fared, fearing the worst … It’s so good to know she’s been doing so well for herself and has been reunited with her oldest at least. It always struck me how terribly desperate she must have been to leave 3 young kids behind; hell for any mother (and for the children as well …. I’m ashamed to say I never realised that ….).

My feelings for mr Good are such that I threw out his book when I first say the documentary on Yarima’s homecoming. But it’s great to know how David seeems to manage balancing both worlds. Kudos and good fortune on your endeavors to help the indigenous people of the Americas, from a nurse in Holland.