In 2001, a graduate student named Charles Zidar attended the Primer Congreso Internacional de Copán — entitled Ciencia, Arte y Religión en el Mundo Maya — where he listened to a lecture on the polychrome ceramics of the Classic Maya, AD 250–900, presented by Dorie Reents-Budet, an expert on Mayan ceramics and curator of the Art of the Ancient Americas at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

|

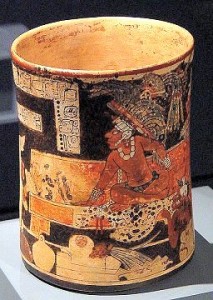

| Classic Maya vase depicting a scene of the royal court |

The paintings on these ceramics provide important information about the daily life of the Maya elite class, Reents-Budet said; they depict the decorations that adorned their now bare stone palaces, and the perishable interior furnishings that have not survived in the archeological record — curtains and throne covers of cloth and jaguar skin; ceramic, gourd, wood, and basketry containers; books; regal costumes; musical instruments; scented torches. And she mentioned, in passing, that the botanical motifs with which many of these ceramics were decorated remained unidentified.

This remark inspired Zidar, a natural historian and archaeologist, to focus his research on plants illustrated on Maya ceramics, culminating in the creation of a botanical resource database of the plants depicted in Classic Maya art, with the goal of rediscovering currently unknown or forgotten plants that had been important — symbolically, ritually, or economically — to the ancient Maya.

Painted and sculpted images of whole plants, leaves, fruits, and flowers are represented on many Maya artifacts; the “breath soul,” the carrier of life, was often conceptualized as a flower. However, “despite the importance of plants to the ancient Maya and the many advances in understanding ancient Maya iconography and hieroglyphs,” Zidar says, “there has been scant identification and interpretation of botanical motifs in Classic Maya art. Many Classic period monumental and personal artworks feature plants, the rich variety of imagery reflecting that of the natural environment.”

|

|

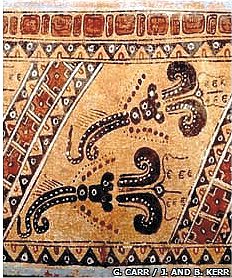

| Trunk spines of Ceiba pentandra (left) depicted on a ceremonial incense jar | |

Now some of this research has appeared in an article, co-authored by Zidar and botanist Wayne Elisens, and published in the journal Economic Botany.

This first analysis focuses on artwork produced in a single geographic area — the southern lowland region of the Maya, located in the modern countries of Belize, Guatemala and Mexico. In particular, too, the authors searched for depictions of bombacoids, a diverse family of neotropical trees characterized by swollen or spiny trunks and big, colorful, conspicuous flowers with long folding petals. The goal was to see which of these plants were important to the culture, and why.

The study involved evaluating more than 2,500 images of Maya ceramics from the collection of Justin and Barbara Kerr, curated by the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, located in Crystal River, Florida. “It has amazed me that so many plants are depicted,” said in a BBC interview. “These plants are not as stylized as previously thought, and thus you can name the plant family, genus, and even the species.”

|

|

| Flower of Quararibea sp. (left) painted on a vessel used for sacred chocolate | |

For example, among the discoveries were numerous depictions of the kapok tree, Ceiba pentandra, which grows around 150 feet high, and was sacred to the Maya as the “first tree” or “world tree,” thought to stand at the center of the earth. The thorny trunks of the Ceiba tree were found to be represented on ceramic pots used as burial urns or ceremonial incense holders.

“The Maya have lived and used rainforest plants to heal themselves for thousands of years,” Zidar said in a BBC interview. “We are just beginning to understand some of their secrets.” He continued: “By determining what plants were of importance to the ancient Maya, it is my hope that identified plants can be further studied for pharmaceutical, culinary, economic and ceremonial uses.”

- Previous Post: The Shulgin Documentary

- Next Post: Salvia on Schedule

- More Articles Related to: Indigenous Culture, Plant Medicine, Research Studies, Sacred Plants, The Medicine Path

My research at mushroomstone.com presents visual evidence that both the hallucinogenic Amanita muscaria mushroom (SOMA of the New World) and the Psilocybin mushroom were worshiped as gods in ancient Mesoamerica. These divine mushrooms were so cleverly encoded in the religious art of the New World that prior to this study they virtually escaped detection. The study, a very large document containing over 300 images, is presented in three parts (the Home Page, Part I and Part II).

It was inspired by a theory first proposed by my father, the late Maya archaeologist Dr. Stephan F. de Borhegyi, (more commonly known as Dr. Stephan Borhegyi,) that hallucinogenic mushroom rituals were a central aspect of Maya religion. He based this theory on his identification of a mushroom stone cult that came into existence in the Guatemala Highlands and Pacific coastal area around 1000 B.C. along with a trophy head cult associated with the Mesoamerican ballgame.

Carl de Borhegyi

I lived in Belize for many years and got to know some of the medicne women and men. I learned some of the traditional medicines and used for my children when they were sick or needed nurtitional supplements. china root, old mans back, talla walla, sourecy, guinee hen root, gwengao, yama bush ,contribo and many many more. Beth Fairweather

My husband and I went deep into the jungles of Belize seeking the ayahuaca plant to see if it was growing there. Our curanderos did not seem to be familar with it or perhaps know it by that name. Does any one know if it grows there. If it does where was it found? Beth Fairweather

I am from Nicaragua looking information about Calycophyllum candidissimum used by mayans or other indigenous culture (different period of time) in Central América and Nicaragua. Thank you very much.