For most of his life, psychologist Carl Gustav Jung enjoyed telling the story of the Solar Phallus Man — the designation was conferred by historian Sonu Shamdasani — and often claimed that the story was the single most compelling piece of evidence for his theory of the collective unconscious.

The Solar Phallus Man was actually a patient named Emile Schwyzer, diagnosed with what was then called paranoid dementia, who had been committed to the Burghölzli Clinic in Zürich in 1901 after an attempted suicide. Schwyzer had been in and out of other institutions for decades. As Jung told it, he had begun treating this patient in 1906. Schwyzer reported a particularly striking hallucination in which the sun had an upright tail — “similar to an erect penis,” Jung adds parenthetically — which moved back and forth when Schwyzer moved his head with his eyes half shut, and this motion caused the wind to blow. This is how, Schwyzer explained, he could control the weather.

|

| Carl Gustav Jung in 1906 |

This hallucination, Jung says, remained unintelligible for a long time, until he became aware of remarkably similar symbolism in a Mithraic liturgy, part of the Greek Magical Papyri, that had not been published until 1910. Here the ministering wind was said to originate from an αυλός — a pipe or tube — hanging from the disc of the sun, which could be seen by looking from east to west. Schwyzer was a store clerk with no higher education, unlikely to have read or heard about such an esoteric symbol. Even more, he had described it to Jung before it had even been published. Where could it have come from if not from a collective unconscious?

Now this is a hell of a story, and we can understand why Jung enjoyed telling it. But the story has a number of problems.

Let’s start with the dates. Schwyzer’s vision had in fact been conveyed not to Jung but rather to Jung’s twenty-four-year-old student Johann Honegger, who had interviewed Schwyzer over two months in 1910, while Jung was in the United States, and three years after Jung had stopped treating the patient. Honegger presented the vision of the solar tail or penis — along with a great number of other apparently mythic visions and beliefs he had been told by Schwyzer — at the second International Psychoanalytic Congress in Nuremberg in March 1910. Apparently Schwyzer had told none of this material to Jung. Honegger unexpectedly committed suicide with a morphine overdose in March 1911.

Jung published the solar penis story in Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido in 1911. In that text, Jung credited the discovery of the hallucination to Honegger, and he cited two sources for the Mithraic liturgy it purportedly matched — a 1907 English translation and a 1910 German translation. In fact, as Jung subsequently discovered, the 1910 German translation was the second edition of a work that had first been published in 1903, and upon which the English translation had been based. After the original citation, Jung stopped referring to the 1907 English translation, and he never referred to the 1903 edition of the German translation at all.

In Jung’s 1952 English-language revision of Wandlungen, now entitled Symbols of Transformation, Honegger disappears altogether. Here it is Jung who “once came across the following hallucination in a sczhizophrenic patient.” As late as 1959, in an interview with John Freeman on the television program Face to Face, Jung insisted that he had heard the solar penis vision in 1906 and that the Mithraic liturgy was first published four years later in 1910. In this version, Schwyzer had grabbed Jung by the lapels and pointed at the sun, saying it had a penis. If Jung moved his head from side to side, he would see. It was this penis that caused the wind.

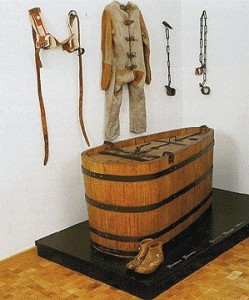

|

| Klinik Burghölzli |

It is true that, if Schwyzer was committed to Burghölzli in 1901, then he clearly would have had limited access even to the German translation of 1903. On the other hand, as Richard Noll has pointed out, the image of a solar penis had already been discussed in Friedrich Creuzer’s massive compendium of ancient symbolism and mythology, the third edition of which was published in 1841, and in Johann Bachofen’s 1861 text on matriarchy. Both of these books had a profound and enduring effect on German popular culture. And there is no way of telling what Schwyzer may have heard from other Burghölzli patients, many of whom were in fact well educated, and at least some of whom had interests, not uncommon among educated German speakers at the time, in ancient religions and symbolism.

But the disappearance of Honegger masks a more serious methodological issue. Shamdasani has recovered the text of Honegger’s 1910 presentation of the Schwyzer material, along with another unpublished article on the same case. Since Jung had by that time ceased his clinical practice at Burghölzli to pursue his mythological research, he had given Honegger the task of retrieving mythic material from psychotic patients at the clinic.

Honegger seems to have pursued this task with a vengeance. Schwyzer, Shamdasani notes, turned out to be “a veritable textbook of mythology.” He told Honegger that the deity was originally feminine, that the dead became stars in heaven, that the earth was flat and surrounded by infinite seas, and that the sun had a penis — or perhaps a tail — that caused the wind. Honegger could not have been more pleased.

And there is good reason to believe that these were far from spontaneous utterances. They were, rather, the result of Honegger’s probing. How do you know that the seed body was always feminine? Honegger asked. Can you also make wind? How do you do it, when you want to make rain? Schwyzer, undoubtedly bored and lonely, would have been only too happy to oblige this interested and sympathetic listener. Indeed, given Jung’s admiration for the work of Creuzer, it is not unlikely that his student Honegger had himself read the book and its section on the solar penis.

|

| Chains, straitjacket, cell belt, and covered bath tub formerly used to restrain patients at Burghölzli Clinic |

Carl Meier, a psychiatrist who had known Schwyzer personally and had reviewed his entire medical file, said that he had never succeeded in finding out the function of the solar penis in Schwyzer’s hallucinations. In fact, he said, by the time he knew him, Schwyzer no longer even remembered it.

Putting all of this aside, the problem is that Schwyzer’s hallucination in fact provides no evidence at all for Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious.

The most important thing about the unconscious is that it is… well, not conscious. How then do we become conscious of — forgive the spatial metaphor — its contents? For Freud, there is no such thing as nonverbal thinking; the unconscious is accessed through words. For Jung, on the other hand, the unconscious is accessed through images. These images appear to us in dreams, fantasy, visions, imagination, and hallucinations. These images are how the unconscious communicates with us.

Again contrary to Freudian psychoanalysis, Jung maintained that, underneath this unconscious, there lay another unconscious, which he called first the phylogenetic and then the collective unconscious. As Shamdasani has demonstrated, the idea of such a phylogenetic or racial unconscious was congruent with so many elements of late-nineteenth-century European thought that it could, he says, almost have been regarded as a commonplace.

For Jung, this collective unconscious is not filled with images. It is filled with archetypes. Jung likened these archetypes to Kantian categories — that is, to a priori conditions for possible experiences. Jung proposed extending the Kantian idea of the logical categories of reason to the production of fantasy; the archetypes, Jung says, are “categories of the imagination.”

Archetypes thus are form without content; they are possibilities of images. Although they are themselves without content, they are often, on the basis of the images whose form they provide, named after mythological figures — the Hera archetype, for example, or the Wise Old Man archetype; or they may be named for some abstract theme, such as the archetype of engulfment or the archetype of rebirth.

We can distinguish archetypal images from ordinary images because archetypal images appear to us on a wave of emotion; they possess salience and depth; they are numinous and mysterious. It is these same archetypal images that appear as motifs in myths, legends, fairy tales, literature, and art around the world, arising out of the same set of archetypes in the shared collective unconscious. As Joseph Campbell famously put it, dreams are private myths, and myths are public dreams.

|

| Jung in 1910, standing outside Burghölzli Clinic |

There is thus a distinction between an archetype and an archetypal image, a distinction that Jungians — and even Jung himself — have often failed to maintain consistently. There is no access to the archetypes of the collective unconscious; they are transcendental and unrepresentable. All we have are archetypal images, which conform to the a priori conditions imposed by their archetypes. The collective unconscious is a negative borderline concept, just as unknowable as the Kantian thing in itself. We know of the archetypes only through a form of transcendental deduction from numinous images.

Here is an example of how this works out in practice. In psychoanalysis, a dream narrative is analyzed. The patient tells the story of the dream, free associates from that material, relates the dream content to events in childhood. In Jungian analysis, dream images are amplified. The patient — often with active input from the therapist — explores the meaning of the images, not only personally but also historically and transculturally in myths, fairy tales, art, and literature. Amplification is thus a hermeneutic process — a quest for meaning that leads the patient beyond the personal to the wider human and cultural context of the dream material.

So important has this process been that it has had an institutional effect — the development of analytical psychology clubs in urban centers, which are essentially libraries of scholarly resources on myth and religion, where analysts and selected patients can jointly pursue amplification of the patient’s dream and fantasy images.

But it is when such amplifications are used — like the hallucination of Solar Phallus Man — to argue for the existence and nature of the collective unconscious that serious methodological and conceptual issues arise.

Methodologically, it is virtually impossible to find uncontaminated material. The clients of Jungian therapists, including those of Jung himself, have been largely self-selected. They enter Jungian analysis because they have read about its interest in myth and dream, and because this reflects their own often long-standing interests. Jungian analysts, too, actively participate in image amplification. That is why Jung considered the Solar Phallus Man so important. It was, he thought, a hallucination that could not conceivably be accounted for by cryptomnesia or forgotten outside sources.

And the idea that numinous images are somehow shaped by transcendental a priori archetypes raises a whole series of troubling conceptual issues.

The claim that the same image has arisen in people far separated in space and time — a Burghölzli patient in 1910, say, and a Mithraic writer fifteen centuries earlier — is meaningless without criteria for deciding when two images are the same and when they are not. Schwyzer’s sun is variously described as having either a tail or a penis pointing up; the Mithraic liturgy speaks of the sun as having a pipe or tube hanging down. There is no way to know whether this matters.

|

| Jung in 1959, on Face to Face, telling the story of the Solar Phallus Man |

Moreover, there is clearly no one-to-one relationship between archetype and image. A single archetype can give rise to any number of archetypal images; and a single archetypal image may — or perhaps may not — be of two different archetypes at the same time. If the relationship between archetype and image is many-to-many, then the relationship between an image and any particular archetype becomes indeterminate. In the same way, we have no criteria by which to rule out the possibility that the widely separated solar penis images were coincidentally similar images from two different archetypes.

Just how many archetypes are there? There appears to be no constraint on their number or nature. Steven Walker, a scholar of comparative literature sympathetic to Jung, says that “the list of archetypes is nearly endless.” There can be an archetype for just about any possible human situation, it seems; and conversely each archetype can produce an indefinite number of archetypal images. And apparently we can make up archetypes at will. Is there a solar penis archetype? That seems surprisingly narrow for a fundamental a priori category of the imagination. A few minutes thought can yield a dozen archetypal possibilities, from masculine generativity to magical control of the weather. In the endless list of archetypes, how do we decide?

And if the person who has produced the numinous image gets to decide with which mythic motif or fairy tale situation it most clearly resonates, then it is not clear why we need to postulate transcendental archetypes of the collective unconscious at all.

Psychologist James Hillman faced this issue squarely, and he chose to eliminate the noun archetype altogether, while preserving the adjective archetypal. The problem, he says, is that Jung moved “from a valuation adjective to a thing and invented substantialities called archetypes… Then we are forced to gather literal evidence from cultures the world over and make empirical claims about what is defined to be unspeakable and irrepresentable.”

But we do not need to take the idea of the archetypal in this reified sense. Any image can be archetypal, Hillman says; it need only be given value — archetypalized or capitalized — by the person experiencing it. “By attaching archetypal to an image,” he says, “we ennoble or empower the image with the widest, richest, and deepest possible significance.”

|

| James Hillman |

This view informs Hillman’s approach to dreams, which is not hermeneutic, as it is for Jung, but rather phenomenological or, in Hillman’s term, imagistic, image-centered. “To see the archetypal in an image,” he says, “is not a hermeneutic move.” He thus sees little value in traditional amplification. “Hermeneutic amplifications in search of meaning take us elsewhere, across cultures, looking for resemblances which neglect the specifics of the actual image.” Instead of asking how an image is related to an archetype, the patient begins with and concentrates on images in all their multiple implications — a process psychologist Stephen Aizenstat calls animation, “entering the realm of the living dream.” The idea is to personify the image, ask it questions, interrogate its purposes, engage it as a teacher — even identify with it and question its meaning as one’s own. Hermeneutics is replaced by imagination.

Still, if what we are looking for is the meaning of images — in dreams, visions, imagination, fantasy — then it is worthwhile, I think, to pursue that meaning wherever we can. We do not need to postulate a collective unconscious or the existence of archetypes to pursue that meaning across cultures and through history, or to place our own images in the vast context of human suffering and transformation. The purpose is to give our dreams and visions life-giving depth, overflowing with meaning and power — what Hillman calls “unfathomable analogical richness.”

Nor do we need to limit this pursuit to images from the unconscious. In a dream I see a smiling child, I stumble over a rock, I stand in the rain; and I seek out what these images mean, I engage them and seek their counsel. A smiling child, a rock, the falling rain deserve no less inquiry, no less depth, just because we have classified them as real.

- Previous Post: Amazonian Gastronomy

- Next Post: On the Origins of Ayahuasca

- More Articles Related to: Research Studies, Shamanism

This is an exceptionally clear presentation of the Jungian notion of the collective unconscious, and of some of the suspicious circumstances that led to it. I wonder if the manipulation and subsequent valorization of Schwyzer’s vision – if indeed he had it at all – can be seen as a potential fatal flaw or underpinning in Jung’s thinking? You write, “The claim that the same image has arisen in people far separated in space and time … is meaningless without criteria for deciding when two images are the same and when they are not.” This is the same question archaeologists and historians ask when they see roughly similar phenomena spread widely across space and time: What’s the mechanism of this transmission? Reliance on the notion of a collective unconscious is not satisfying to them, because cultures with extreme differences would almost certainly not share the same territory within the unconscious. Or so the thinking goes. Is it possible, I might ask, that Europeans or Norte Americanos can comprehend the vision of a jaguar under the influence of ayahuasca and Peruvian icaros with the same mythic sense or weight as mestizos in the Upper Amazon, with what I presume is their limited literacy and exposure to the Euro-American collective unconscious?

Fred wrote, “Is it possible, I might ask, that Europeans or Norte Americanos can comprehend the vision of a jaguar under the influence of ayahuasca and Peruvian icaros with the same mythic sense or weight as mestizos in the Upper Amazon, with what I presume is their limited literacy and exposure to the Euro-American collective unconscious?” I definitely think so. Have you tried these things? What do you think? To be clear about it, I never had jaguar visions, but a few possession-type experiences (tactile, as opposed to visual or auditory, hallucinations?), where I felt jaguar energy in my body, unbelievably strong, and gave voice to this sensation. The indigenous people I was staying with made it clear to me that what was happening to me was what happened to them under similar circumstances. I don’t know if that has anything to do with anything Jung was talking about. At the time, to me, it made sense in terms of a purely indigenous worldview involving spirits.

From what I’ve read of trip reports by ayahuasca drinkers, visions of snakes and jaguars are not as common when they drink outside of the jungle.

Nathan, thanks for your very good message. Yes, I have tried “these things,” and in my (limited) experience feel that it’s difficult to move from an orientation in one realm of the collective unconscious into another one in which one has not been toilet trained, mythically. I agree with you that it’s far easier to accomplish this when you’re actually on that soil, in the jungle. The power of the local deities is so much stronger, more imminent, in their own environment. No doubt, a Norte Americano can experience “jaguar energy” in Canada (for example), but to get up close and personal with the inner jaguar, you might have to be in South America. I hope to be proven wrong on this sometime.

This isn’t my area of study but I find it fascinating – and I guess if my biases were known I probably believe in something like the Jungian collection unconscious on the basis of personal experience. It seems as if my personal experience is unlike Fred’s, in that I tend to do religious practices geared towards generating one kind of experience (the input is Catholic Christian and I expect Catholic Christian output) but when everything gets processed by my mind and comes out as dreams or hallucinations or whatever I generally end up with it mythological expressions in terms of other traditions (and sometimes traditions I’m at best only minimally familiar with). This is actually a substantial reason why I got into the professional study of Asian religions – I wanted to figure out why I would say rosaries to Mary and end up with dream visions of Kali or Kuan Yin. I certainly didn’t do substantial toilet training in Asian religions or have strong cultural influences leading me to interpret my experience in that matter – maybe that’s true now, but it wasn’t true until perhaps 10 years ago tops.

I’m a little annoyed by some methodological considerations in this piece – Steve seems to demand a standard of clinical objectivity I think most researchers in the social sciences today would believe can never be met. We have our own version of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle at work in that most (all?) investigations with human informants result in a confirmation loop – the informant socially bonds with the investigator showing them attention and tells them something like what they want to hear. This is worse in clinical situations (such as psychotherapy, Jungian or otherwise) because people approach these situations with the expectation that there is something wrong with them that therapy can fix (a form of self-selection bias) and the therapist is biased to interpret symptoms in terms of treatable conditions it is in the purview of his/her professional competence to fix (a form of confirmation bias). Your Freudian analyst is never going to diagnose susto, even in a Hispanic patient manifesting symptoms for which that’s a culturally-appropriate diagnosis. Clinical investigators are approached by people who feel they have a condition that a certain kind of expert can treat, and the experts have an interest in acting accordingly. To call this bias is perhaps a misunderstanding of what is at work in any act of knowledge, which is more like a matter of negotiating agreement within a particular regime of interpretation than providing an “objectively” valid interpretation of facts.

hi steve,

this is a challenging article. As for the phallus hallucination, i related it to the birkeland currents : http://www.thunderbolts.info/tpod/2008/arch08/080717stringtheory.htm –then there’s some UFO stuff linking sun and UFO’s.

I digged it because i drew a comic book with sun rays turning mad people–then there too these studies with solar storms and psychotic breaks. I thought about on the collective unconscious at the time, because when i draw it i had no notions about anything at all that–i was only a weirdo smoking pot. Anyway, and after your experience with shamanism, do you feel jung’s concept or anything similar is wrong?

I recall too reading about a guy doing lots of psychedelics and talking to living archetypes–i think it was on Zoe7’s second book.

thanks

Fred, forgive me for saying this, but if you want to be proven wrong, you may need stronger drugs, preferably within the context of a righteous ceremony. Some people discount entheogens, but from what I’ve experienced, they’re powerful tools for stripping away social conditioning (don’t worry, it comes back) and returning to the state of being an eternal soul who happens to be residing in a body at the moment.

+Wulfila, you write “Clinical investigators are approached by people who feel they have a condition that a certain kind of expert can treat, and the experts have an interest in acting accordingly. To call this bias is perhaps a misunderstanding of what is at work in any act of knowledge, which is more like a matter of negotiating agreement within a particular regime of interpretation than providing an “objectively” valid interpretation of facts.” I had a class many years ago on “Power Dynamics of Ritual Healing” and one of the points that came up among the ethnographers we read was that a big part of (shamanic) healing was coming up with a narrative that made sense to the healer and the patient. For instance, the patient was driving and nearly had an accident, and part of the soul jumped out, so we have susto, and we can retrieve the soul through our procedure.

I was just discussing matters related to the collective unconscious with Steve via e-mail. I want to paste some text below because it works around to Kali and Kuan Yin. Steve and I got on to Jung’s idea that there were various racial or ethnic unconsciouses, which didn’t sound completely nonsensical to me, either because we consciously identify with our heritage, or because we may have some more subtle intellectual connection with our ancestors. I mentioned a couple of experiences that had made me think the second possibility could be true, and Steve said they could be examples of cryptomnesia. I admitted he was right, and went on in the following vein:

“A really clear cryptomnesiac experience I had in a vision was being on Pluto, and looking back at the sun, which appeared as simply the brightest of the stars in the sky. A couple years later I found that Carl Sagan had written a passage inviting the reader to imagine being on Pluto and seeing the sun that way, and it was in something I had read years earlier.

“Of course, it’s possible to flip the causality around and say that I read the Sagan passage as a boy because I would one day have the real experience as a man.

“That, to me, is ayahuasca logic….

“Similarly, every encounter I had with cats or with cat energy or even with things like photos and videos of jaguars, I came to see as an approach of the jaguar spirit to my soul, one step closer each time.

“It’s like +Wulfila’s visions of Kali and Kuan Yin. He must have known a little about them before seeing them in his visions. If we take the intellectual path that the ancients took, and conceptualize these as disincarnate forms of consciousness coexisting with but a little superior to our own, well then of course they can approach us at will, and in their own ways, by appearing to us in books and in paintings.

“I’m not saying this is all true, I’m just saying it’s consistent with the evidence that we have.”

N

Wow, Nathan, another interesting message. First of all, I would like to see the syllabus for that course titled “Power Dynamics of Ritual Healing.” That aside, it’s likely that stronger drugs would only lead to greater encounters with cryptomnesia (thanks for this word). One’s discriminative intellect must be in firm control to keep the drug from leading us down the path of cryptomnesia. This might be why virtually all philosophical systems, in Asia anyhow, do not regard memory as a legitimate means of proof (pramaana). I get your point, though, that like engenders like. The Siamese cat sitting on my lap as I write this does surely bring me closer to jaguar energy that could fully materialize, become “my own,” with a stronger entheogen under the right ritual circumstances, so long as I don’t get sucked into errors such as cryoptomnesia. A question, I guess, is whether cryptomnesia is always indicative of false knowledge, or whether it can in fact lead one into someone else’s realm of collective unconscious? Maybe, in fact, that’s a legitimate mode of possession…

Lots of interesting material. Responses in no particular order:

1. A methodological question. As there is no way to disprove the cryptomnesia hypothesis once it’s been offered because it’s always possible to postulate that someone “must” have had previous cultural exposure to something to have a religious experience of it even if he/she asserts otherwise, what does the hypothesis really prove – beyond the fact that the person offering the cryptomnesia hypothesis subscribes to an explanatory paradigm in which the collective unconscious is ruled out a priori and you need a more “rational” explanation? I’m all for confirmation loops where informants and investigators conspire to provide explanations to which both can agree, but this particular one sounds like it could serve as the basis for a kind of cognitive imperialism privileging Western rationalist over traditional religious accounts. Is this fair? If it’s fair, is it troubling? Why or why not?

2. Your “Power Dynamics in Ritual Healing” course sounds fascinating. I think it probably helps illustrate the insightful connections Steve Beyer drew between Heidegger (and possibly many other thinkers broadly termed “postmodern”) and shamanism. At least, there’s a fundamental parallel in the epistemologies at work – both seem to be about negotiation to produce shared interpretations within an agreed upon paradigm of interpretation. I wonder if the defining difference between the classical modernist scientific paradigm and postmodern or traditional healing paradigms is found precisely in this question of relationship – modernist scholars try to produce “objective” accounts of reality they can force others to agree to for their own good, rather than hashing out and ritually performing a temporary consensus about reality that can lead to healing?

I’m just thinking out loud – this may be a little disorganized.

Very interesting conversation.

Would someone please tell me the written source for the Solar ray/tube/penis vision. Preferably not in the CW. If it is in MDR could you tell me where.

Thank you so much!

Christine Houde

Fred, forgive me for saying this, but if you want to be proven wrong, you may need stronger drugs, preferably within the context of a righteous ceremony. Some people discount entheogens, but from what I’ve experienced, they’re powerful tools for stripping away social conditioning (don’t worry, it comes back) and returning to the state of being an eternal soul who happens to be residing in a body at the moment.

+Wulfila, you write “Clinical investigators are approached by people who feel they have a condition that a certain kind of expert can treat, and the experts have an interest in acting accordingly. To call this bias is perhaps a misunderstanding of what is at work in any act of knowledge, which is more like a matter of negotiating agreement within a particular regime of interpretation than providing an “objectively” valid interpretation of facts.” I had a class many years ago on “Power Dynamics of Ritual Healing” and one of the points that came up among the ethnographers we read was that a big part of (shamanic) healing was coming up with a narrative that made sense to the healer and the patient. For instance, the patient was driving and nearly had an accident, and part of the soul jumped out, so we have susto, and we can retrieve the soul through our procedure.

I was just discussing matters related to the collective unconscious with Steve via e-mail. I want to paste some text below because it works around to Kali and Kuan Yin. Steve and I got on to Jung’s idea that there were various racial or ethnic unconsciouses, which didn’t sound completely nonsensical to me, either because we consciously identify with our heritage, or because we may have some more subtle intellectual connection with our ancestors. I mentioned a couple of experiences that had made me think the second possibility could be true, and Steve said they could be examples of cryptomnesia. I admitted he was right, and went on in the following vein:

“A really clear cryptomnesiac experience I had in a vision was being on Pluto, and looking back at the sun, which appeared as simply the brightest of the stars in the sky. A couple years later I found that Carl Sagan had written a passage inviting the reader to imagine being on Pluto and seeing the sun that way, and it was in something I had read years earlier.

“Of course, it’s possible to flip the causality around and say that I read the Sagan passage as a boy because I would one day have the real experience as a man.

“That, to me, is ayahuasca logic….

“Similarly, every encounter I had with cats or with cat energy or even with things like photos and videos of jaguars, I came to see as an approach of the jaguar spirit to my soul, one step closer each time.

“It’s like +Wulfila’s visions of Kali and Kuan Yin. He must have known a little about them before seeing them in his visions. If we take the intellectual path that the ancients took, and conceptualize these as disincarnate forms of consciousness coexisting with but a little superior to our own, well then of course they can approach us at will, and in their own ways, by appearing to us in books and in paintings.

“I’m not saying this is all true, I’m just saying it’s consistent with the evidence that we have.”

N

What an interesting conversation about the Solar Man.

This may seem to be dream, but it’s a living experience that confirms, to me, that the symbols of the Solar Pahllus Man is in an image that appeared to me and when I took the photograph I had no knowledge of the Solar Phallus Man.

Some of the images are accessable through Google and input “The Solar Phallus Man”.

I had the photograph of the image and have been interested In Jung for many years and when I read about the Solar Phalllus Man I was tempted to associate the image with that story as the standing man did have a phallus,

The area above his shoulders was vague. However, for many yeas I was sure that some how that it would become move visible. When Kodak produced the first do it your self photo machine for the public it took a negative as digital cameras had not yet be produced. I placed the negative in the machine and it had a choice of many filters. The last filter was the ultraviolet and that brought out the detail. unknown to me this filter is used to in criminology go bring out detail in protein.

What I saw then shook me to my core and has instilled the belife the Jung was right when he wrote of the Universal Unconscious and the power of a symbol.

Any questions or comments will be answered.

what did you see?

I have the understanding that the collective unconscious contained all past, present, future knowledge, so could accommodate all belief patterns (god if you like). So surely the CO would communicate with us in a form that we could recognize and use to better our spiritual and physical life. I have undergone shamanic ceremony in Indonesia (without drugs) and have used DMT and other substances. The ceremony rocked me far deeper and took me to the edge. My dreams and strange behaviors animals would display in front of me radically increased. Also Jung’s writings came to me (via synchronicity). It took years but I am now my real self, totally cleansed. Thank you Jung for being a huge part of that process.

Hi Steve,

Thanks for keeping up this wonderful and wide-ranging public discourse on ayahuasca.

I would really appreciate hearing about your journey from Tibetan Buddhism to the Amazonian medicine way. There’s the bonpo shamanism of Tibet, but doesn’t that extend to the non-dual perspective of Dzogchen? I wonder if you have experience with a non-dual view in the midst of the ayahuasca realm.

I have many questions trying to understand ayahuasca shamanism in light of the eastern teachings, in light of going beyond samsara (are ayahuasca hallucinations samsaric? Are some of them not?). Maybe you have some reflections?

Best wishes to you,

John